What the Models Say

The main reference centers indicate that the equatorial Pacific transition is moving between neutral conditions and the possibility of a weak La Niña at the beginning of the Southern Hemisphere summer. The Climate Prediction Center (CPC) estimates a high probability of La Niña for the October–December 2025 quarter, with a tendency to decrease towards December–February (DJF) 2025–2026, when neutrality gains ground again. This means the summer could start under La Niña influence and evolve to a more neutral pattern by the end of the season.

The reading from the IRI/Columbia agrees with this nuance: neutrality dominates the year-end horizon with a slight leaning towards La Niña in late spring and early summer, then gradually returning to neutral conditions in the first quarter of 2026. Practically speaking, in central Chile, this often means less frontal activity and a warm bias due to a combination of a more stable atmosphere and dry soils after spring.

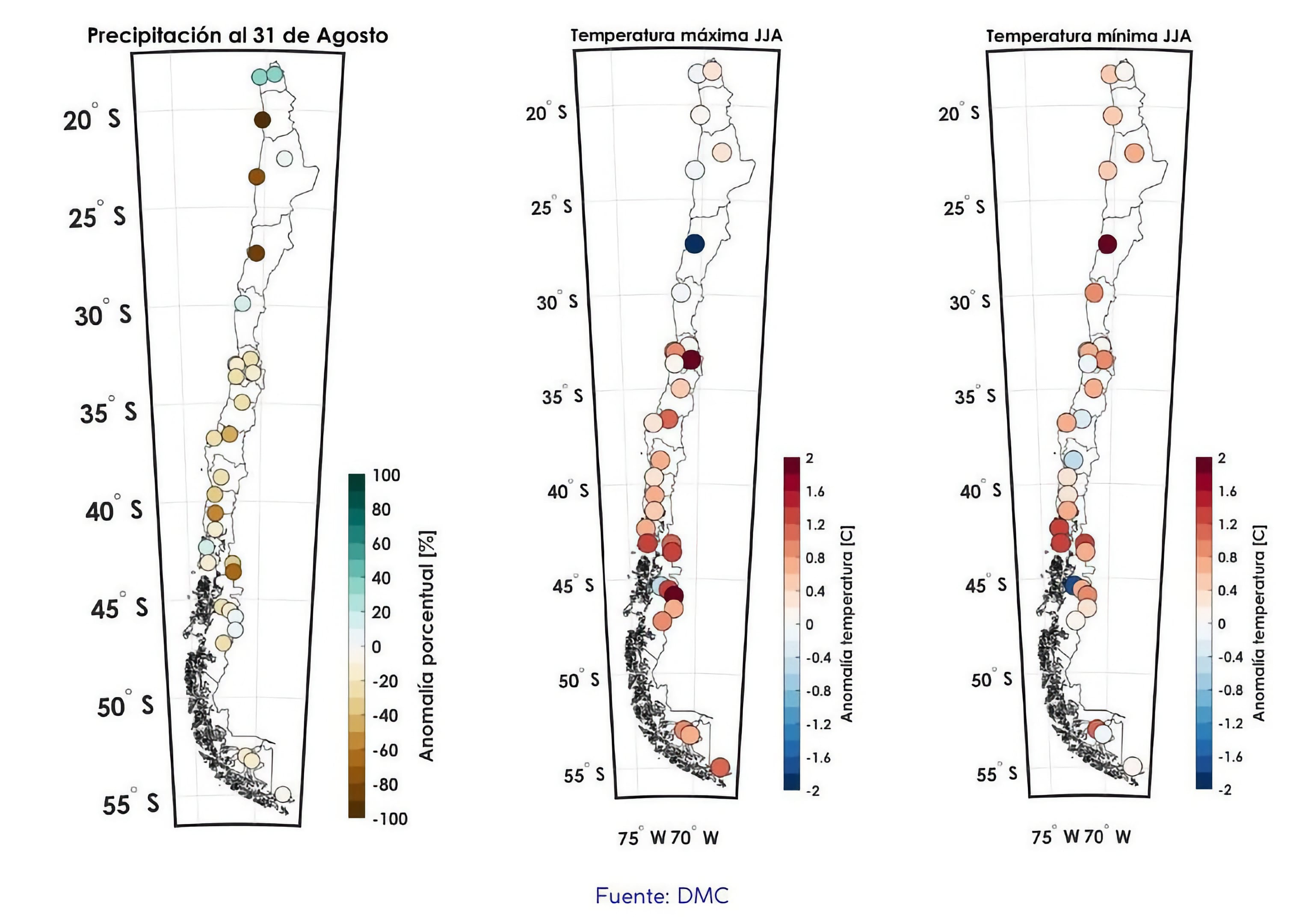

In the short term, the Chilean Meteorological Directorate projected a dryer and warmer spring 2025 across much of the country, with higher than normal maximums from the central valley southwards. That backdrop conditions the summer: less moisture in the soil and vegetation, greater thermal amplitude, and a higher temperature baseline. See projections at Meteored.

This underlying warming doesn't occur in a vacuum. The World Meteorological Organization warns that the next five years will remain among the warmest on record, with a high probability of new records. For agriculture, this means planning seasons where "the extreme" becomes more frequent, even as interannual drivers (El Niño/La Niña) fluctuate.

Finally, the hydrological signal: the DGA of the Ministry of Public Works (MOP) forecasts below-normal meltwater and river flows for spring 2025–summer 2026 in various basins, consistent with the precipitation and snowfall deficit. This anticipates operational restrictions in irrigation, higher pumping costs, and a risk window for crops sensitive to water stress.

What It Means for High-Value Orchards

Cherries. The combination of dry springs and warm summers accelerates development and can advance harvest, with two sides: competitive sizes in well-managed orchards and the risk of softening and pitting in fruit exposed to heatwaves near harvest. In interior areas, episodes of 34–38°C —common in recent summers— increase physiological disorders and require temporary shading, precision irrigation, and evaporative cooling in heatwaves. The lower likelihood of summer rains reduces splitting risk but increases the risk of sunburn and pedicel dehydration, critical for travel condition. The precedents of extreme heat and fire emergencies in the south-central zone during February 2025 remind us of this vulnerability, documented by El País.

Avocado. Avocado quickly reacts to heat and water stress: fruit drop, leaf necrosis, and increased sunburn damage on northwest faces. The summer starting with dry soils and reduced channel recharge increases the cost of maintaining yield potential. Prioritize blocks with better return per cubic meter —based on size and market—, apply canopy whitening with kaolin where management allows, and optimize irrigation through short pulses during high demand hours to cushion losses. (Via: DGA)

Table Grapes. In vines, sustained heat and high radiation favor sunburn and berry shatter if they coincide with dry wind. Red varieties may show incomplete coloration if night-time thermal amplitude shortens; the response includes more shaded canopies, fine load management, and, during heatwaves, micro-sprinkling in pulses to keep cluster temperatures below critical thresholds without saturating the soil. The expected lower water availability reinforces the need for irrigation based on local ETo and moisture probes, avoiding overestimating needs on warm nights.

Blueberries. End-of-spring and early summer heatwaves compromise firmness and bloom. In manual harvests, the operational window decreases during high-temperature hours; in mechanized, the thermal rise translates to a higher percentage of soft fruit. Strategies: 20–30% shade nets, usual irrigation plus cooling curtains pre-fruit and early harvest, maintaining calcium and potassium in high ranges. The projected water scarcity demands scheduling night irrigation shifts when electrical or channel restrictions allow.

European Hazelnut. In warm and dry years, seed fill demands consistent watering. Stress near harvest reduces oil content and increases discard due to "white" or poorly filled kernels. January temperature peaks can intensify fruit abortion in young orchards and aggravate alternate bearing if the plant accumulates repeated damage. Management focuses on early controlled deficit irrigation but without stress during filling; and on crown cooling in prolonged heatwaves to sustain stomatal activity. The signal of low flows compels prioritizing critical sectors and closing hydraulic gaps (losses, uniformity).

Cross-Cutting Risks: Heat, Fire, and Crew Health

Last summer left hard lessons: fire outbreaks, extreme heat, and mobility restrictions in south-central communes. For this season, and in light of a once again warm scenario, it's wise to review prevention and response plans: clean firebreaks, machinery maintenance up-to-date, work protocols on alert days, and coordination with local brigades. The 38–40°C days experienced in February 2025 in parts of Maule and Ñuble illustrate the type of conditions to anticipate, according to El País coverage.

What to Watch Week by Week

The value lies in adjusting the strategy on the ground:

Alerts from the DMC for heatwaves and south wind; while they don't determine the season, they're crucial for the critical days of sun damage or dehydration.

Bulletins from the DGA and Agromet, to monitor flows and agricultural water stress, focusing on basins already recording deficits.

The upcoming summer presents more heat than average in the south-central, just enough water in the channels, and high-value crops demanding a fine touch. With careful planning and well-applied irrigation technology, it's possible to protect size, firmness, and condition, reaching markets with travel-resistant fruit.